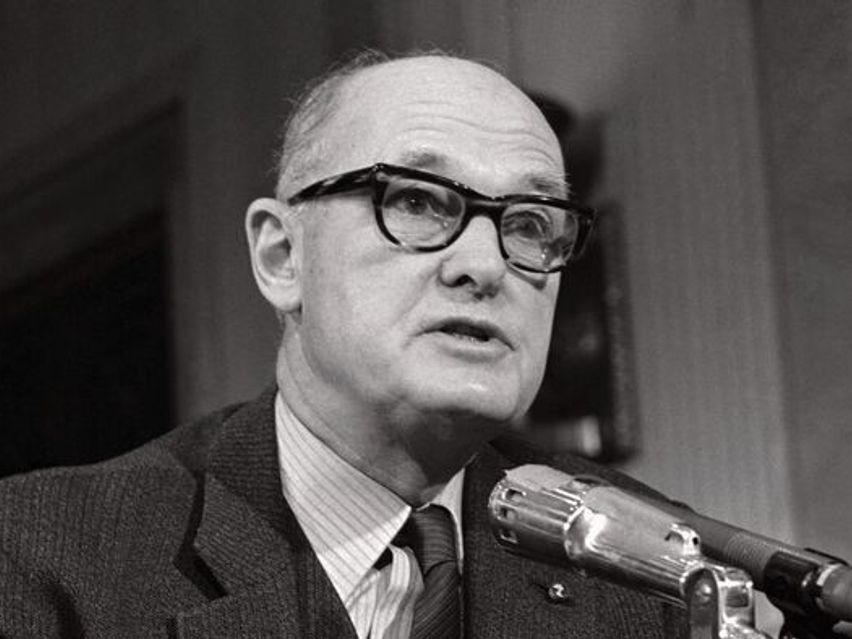

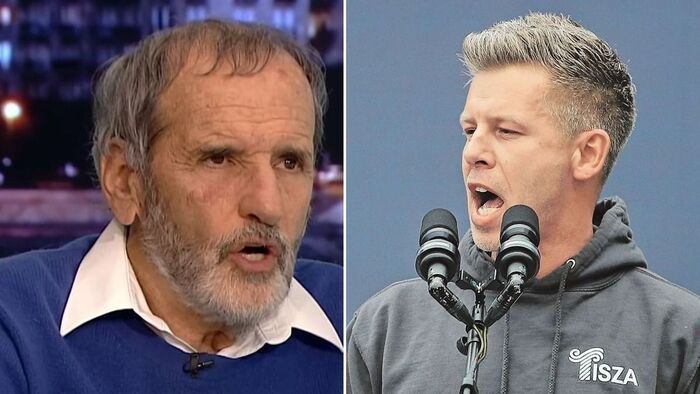

– The Brussels political elite is increasingly pushing for Ukraine to join the EU before 2030, if possible. Critics argue that this poses numerous risks, particularly in agriculture, where it could render life for producers in other member states unviable. How do you assess the current competitiveness of Ukraine’s agricultural sector in EU markets?

– The key question is whether we are assessing Ukraine’s competitiveness, or that of the corporations operating there — companies registered in various parts of the world but investing in Ukraine. Ukraine is a corrupt country at war, with half-ruined infrastructure. A significant portion of its workforce is on the front lines or recovering at home from injuries. Large areas of its farmland are littered with landmines, and some are contaminated with radioactive substances due to so-called "dirty bombs." If we look at competitiveness in this context, the picture is quite grim. However, Ukraine possesses 41.3 million hectares of agricultural land, which accounts for 26 percent of the European Union’s total agricultural land. Of that, 32.7 million hectares is arable land — a full third of all arable land in the EU.

Take sunflower production, as just one example: Ukraine produces 16.8 million tonnes annually, compared to 10.3 million tonnes for the entire European Union. That means Ukraine produces 58 percent more than all 27 EU member states combined.

In addition, the competitiveness of Ukraine is bolstered by the high quality of its soil: 9 percent of the world’s black soil, or chernozem, is found in Ukraine. This gives it an extraordinary advantage. The land ownership structure also appears to tilt the scales in Ukraine’s favor. Unlike in EU member states, large-scale farming operations dominate in Ukraine, with over half the farmland consisting of plots larger than 1,000 hectares. Much of this land is owned by large international holding companies with immense capital and access to state-of-the-art machinery.

– What would all this mean in the long term for agricultural producers in current EU member states?

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!