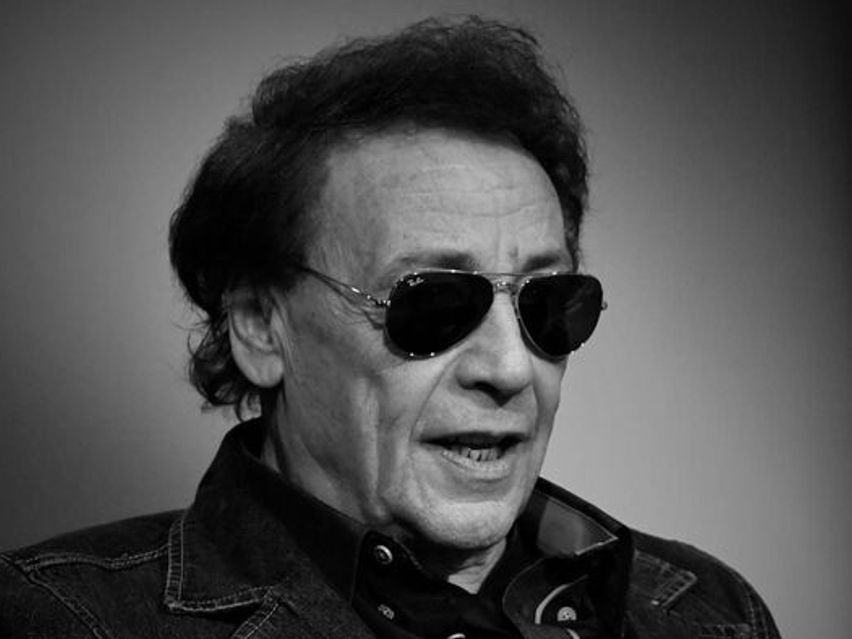

Why doesn't Poland have a prime minister like Viktor Orbán? - asks Lukasz Warzecha, a publicist for the conservative Polish weekly Do Rzeczy. The "brutal answer," he writes, is that there is no need for one.

The majority of Polish voters expect "moral politics, not realpolitik" from their politicians. They don’t want things to be "done" for them; instead, they want to feel morally superior when they cast their votes. Moreover, one of the most significant arguments in Polish public discourse—on both sides of the political spectrum—is the frequent and often senseless reference to Putin. This ultima ratio (final argument -ed.) is used in various contexts, creating a deep divide between Polish and Hungarian politics.

According to the publicist, the lessons of Hungary's historical past have always had, and continue to have, a profound impact on the thinking of the Hungarian political elite, including Viktor Orban. Now, we can draw some basic conclusions from this: there is no place for emotions in international politics. When Hungarians have succumbed to their emotions - as in 1956 - they suffered defeat and paid a heavy price for it. So, they came to the conclusion that instead of emotions, they need strict realism. This is greatly influenced by the fact that Hungarians feel that they are different from other European peoples, if only because of their language, which is unique in Europe.

They are convinced that they can only rely on themselves and must prioritize their own interests, just like the great powers, such as the United States. The Treaty of Trianon - which left millions of Hungarians displaced, outside the country’s borders through no fault of their own - has also contributed to this mindset. The motherland feels a duty to care for them, which is why Hungary has paid special attention to Hungarians living in Transcarpathia since the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war,

– the author writes.

Changed relations

After the Russia-Ukraine war began, Poland’s former ruling party, the national conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, changed its attitude towards Viktor Orban and Hungary. With few exceptions, politicians from Jarosław Kaczyński's party severed ties not only with the Hungarian government but also with the Hungarian embassy in Warsaw. The situation has deteriorated to the point where Polish state services—under the command of Interior Minister Mariusz Kamiński—failed to respond to physical attacks on the Hungarian embassy, such as when red paint was sprayed on the building.

There was, of course, no rational basis for this resentment towards Hungary. Russia’s attack on Ukraine did not change the Hungarian prime minister’s political direction. On one hand, the Polish side acted as if Hungary was obligated to mimic Polish foreign policy, despite the two countries having different resource supplies, positions, dependencies, and priorities. On the other hand, Warsaw seemed to expect Budapest to adopt Poland’s self-destructive, emotion-driven approach of putting all its eggs in one basket and prioritizing the interests of others over its own,

– Lukasz Warzecha wrote, adding that

Prime Minister Orban did what he has always done: he put the interests of Hungary and Hungarians first, including those living in Ukraine under the threat of war.

Hungary, more dependent than Poland on Russian raw materials, has no interest in supporting sanctions on Russia without prior consideration and deeper analysis, even though it has not been able to fully exempt itself from them. Hungary’s "reluctant" approach has had its consequences, most recently with Ukraine cutting off oil supplies to Hungary and Slovakia from the Russian company Lukoil.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!