− Do you remember the day of 24 February, 2022? How did you learn about the outbreak of the war?

− It was not completely unexpected. Various intelligence agencies had been issuing warnings about a possible attack for weeks. However, I can't say that we expected it as even the Ukrainian leadership was trying to calm the public mood. We simply went to work that day, as always. Later, we heard the sirens and the explosions, but in the first hours, it seemed completely unbelievable that war had actually broken out.

− Is there a protocol for such cases?

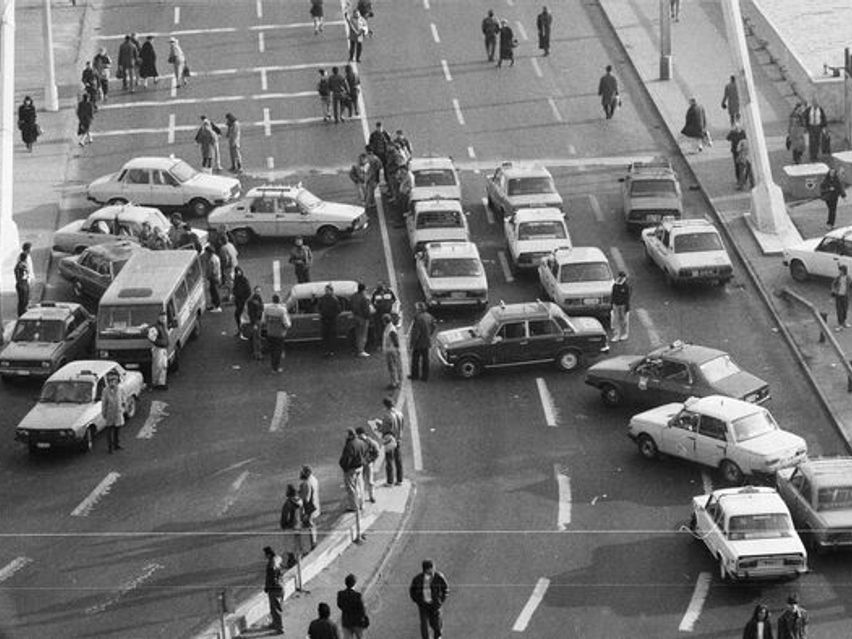

− Of course, we are always prepared for every eventuality. First, I instructed my colleagues to stock up on food and fuel. This became necessary as we moved into the embassy building. We had to do this because there was no way of knowing how the events would unfold. We could have been in for much heavier bombardments and even street fighting. Secondly, the first consequence of any act of war is that people panic and began to flee. So, we also had to make sure that the embassy was a centre where anyone could receive help and find shelter.

− Some countries' embassies, such as the US, had already moved their diplomatic representation from Kiev. Why did you hold out?

We evacuated in three waves. First came the families, so by the end we had very few people left in the embassy. In the meantime, we helped other nations, as several embassies approached us to get their people out of the country. The task was made more difficult by the fact that there was no way of knowing whether the Russians would encircle Kiev. We were pressed for time, as we had to move while there were still clear routes. But there was doubt about what would happen to those, because in war, infrastructure is unfortunately a prime target for attackers and defenders alike. We had to consider whether it was safer to move or to stay. In the end, it turned out that the Russians were not attacking the trains, so safe escape corridors to Western Ukraine could be established.

The moment has finally come when I thought that the risk of encircling the capital was so great that I suggested that we temporarily move the embassy to Lviv.

I understand that some of the Ukrainian government officials had also left Kiev by this time. We evacuated the embassy building, secured the sensitive data, and in March and April we resumed our operation from Lviv with a minimum number of staff. In addition to liaising and monitoring the situation, this soon meant that we mainly had to organise humanitarian aid.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!