"Too many politicians are listening exclusively to their national opinion instead of acting as a full-time European," said Jean-Claude Juncker, former president of the European Commssion, a few years ago. In his own fashion, he quite aptly summarised the political agenda of the globalist, leftist-liberal elite, designating the "populists" as their main enemy. In other words, those who, in search of democratic legitimacy, do dare to say what the majority considers to be true and what common morality (common sense) considers to be right – regarding, for example, multiculturalism, child protection or a military conflict.

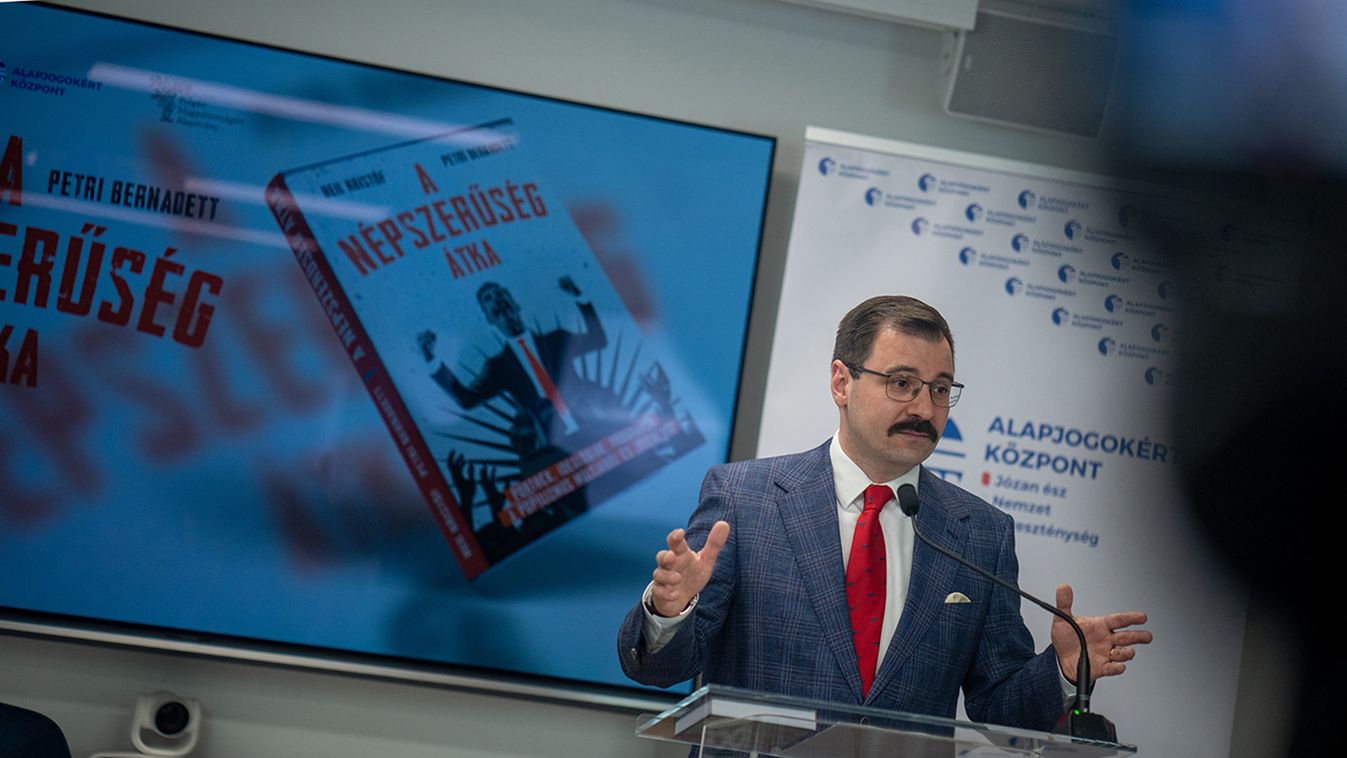

Nowadays, of course, there are many other "scientific arguments" in the mainstream public discourse (see the so-called fact-finding data-based journalism) that present "populists" and populism as the main enemy of the democratic Western culture of knife and fork users (sometimes because they are "Trumpist militants", sometimes because they are "Putinist supporters of peace"). Accordingly, populism is a 'new' trend that fundamentally shatters the established democratic order, destroys the liberal rule of law and deeply oppresses "marginalised", "intersectional", "progressive" identity groups. However, if we look a little more closely at the social manifestations of populist politics, we can see that this interpretative framework is rather out of touch with reality.

Populism is in fact the crossing of postmodern mass society and the mediatised public, their quintessence: the politics of common-sense people constituting a majority, that is, politics that reflects this majority.

It is therefore highly democratic, if democracy is understood on the basis of popular sovereignty. This approach understands nations as "large communities" – at least it seeks points of consensus that bind societies together – rather than as a set of different (minority) identity groups, as postmodern leftist-progressive concepts do. In fact, the liberal conception of democracy calls the "populists" to account for this, because the former does not regard the “rule of the people”, understood in a "more unified" sense, and the majoritarian popular mandate as the source of legitimacy, but considers the liberal "principles and international standards" as such (see the rule of law procedures launched against Hungary).

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!