If ever, now is the time to recall Viktor Orban’s statement made at the end of February 2022 (and repeated several times since), in which he emphasized the importance of strategic calm in a country close to a war zone. As he explained in a televised interview:

The next decade will be about who can create a safe environment for everyday life for their own country and people.

Hungary's prime minister also added that the main question is:

Whether we can responsibly manage the risks of this wartime situation. Whether we can find, every day and every hour, those good decisions that reduce danger and help us stay out of this conflict. What is the decision that best serves Hungarian interests? Because Hungary’s interests come first—and that includes avoiding sanctions that ultimately make us pay the price of the war.

Well, three years of that decade have passed, and the situation and the task at hand remain exactly as the prime minister described them. In fact, things are worse now, and the task has become more difficult. Not only are the two main warring parties moving deeper into war, but so is most of Europe.

And we Hungarians are paying the price of this war, even though we have steadfastly stayed out of it. This cost—i.e., loss—has now reached €20 billion, which is over 8,000 billion forints.

How big is that amount? It’s more than the total pensions already paid out and yet to be paid to Hungary’s 2.5 million pensioners in 2025. If this money were available, pensions could, in theory, be doubled. Furthermore, this amount is more than twice the total 2025 state budget allocation for education, healthcare and family support combined.

If this gigantic sum—together with the billions in EU funds rightfully owed to us but arbitrarily withheld by the Brussels imperial center for political and ideological reasons—were “in our pocket,” then 2025 could truly be a great year for the Hungarian economy and society. But let’s not daydream. It's better to remain realistic.

This realism is reflected in the government's recent decision to revise the 2025 economic growth forecast from 3.4% down to 2.5%, and to raise the annual inflation projection from 3.2% to 4.5%. And these figures may still change—because nobody knows what the coming months will bring. Currently, the only certainty is that external political and economic conditions are worsening: the end of the war and sanctions seems farther away than many hoped, especially around the time of Trump's inauguration. Worse still, the harmful effects of Brussels’s economic sanctions may be amplified by a global trade war, triggered by U.S. tariff hikes—whose consequences are as yet unknowable but likely to be severe.

In this extremely complex and difficult situation, the most important thing is to keep finding those daily decisions that mitigate risk. And for this, we truly need strategic calm and patience, along with an accurate perception and interpretation of reality.

The only problem is that reality is extremely complicated. As the saying goes, every coin has two sides—sometimes even three. On the one hand, Viktor Orban is right when he says:

If you want peace, support the Americans.

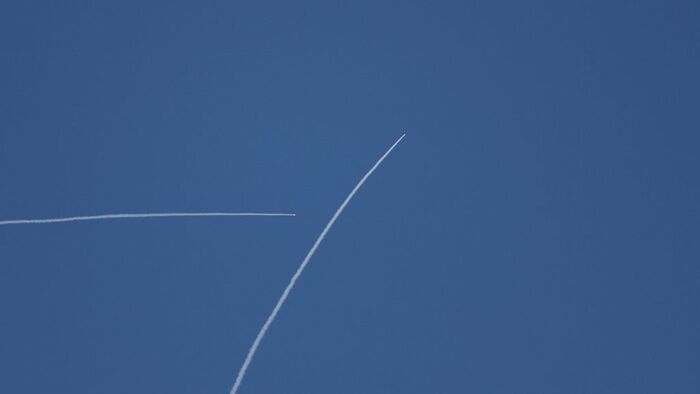

On the other hand, the majority of EU countries—and Brussels itself—seem to be following the advice of ancient Roman military writer Flavius Vegetius Renatus:

If you want peace, prepare for war.

And they are preparing—ever more blindly, vehemently, and at times hysterically. Since Hungary is virtually alone within the EU (at least for now), in siding with the Americans and advocating for peace, this is extremely uncomfortable. After all, Hungary is not part of the United States, but a member state of the European Union—with all the advantages and disadvantages that entails. Lately, we’ve been experiencing more of the latter.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!