Brussels remains committed to bringing Ukraine into the European Union, and to doing so as quickly as possible. Yet Ukraine’s accession carries risks across multiple areas, and in many respects the country stands at odds with fundamental EU values.

The European Commission has repeatedly declared Ukraine’s accession one of its highest priorities. Not even the Ukrainian corruption scandal has shaken Brussels’ resolve; officials already speak as though Ukraine might join in the coming years. To enable this, they are prepared to employ every legal maneuver necessary to move Ukraine onto an accelerated track to membership.

Still, the prospect of EU accession has triggered a long list of legal concerns—some obvious, others more indirect.

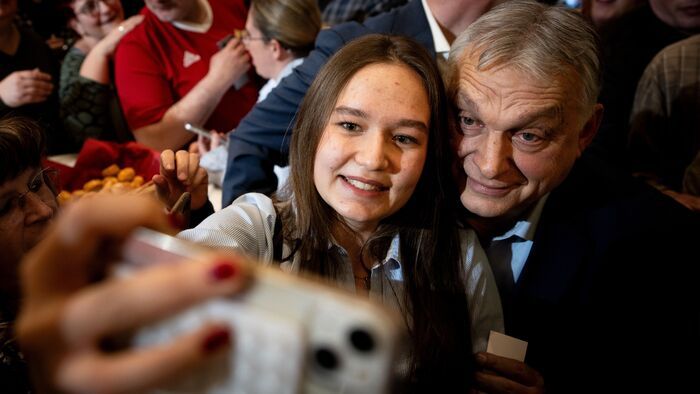

Prime Minister Viktor Orban has repeatedly warned that admitting Ukraine would also mean admitting the war into the European Union. It is also widely known that Ukraine does not treat the minorities living on its territory— including ethnic Hungarians in Transcarpathia—appropriately. On these questions, and on the dangers of Ukrainian accession, we asked for expert analysis from Dr. Lomnici Jr at Szazadveg.

Regarding the possibility of “importing” the war, the constitutional lawyer emphasized that this is not merely one of many aspects of Ukraine’s accession, but the single most important—and one that is routinely underestimated.

The European Union is not merely an economic bloc, but—under the treaties—a political and security collective in which member states undertake obligations for one another’s defense. The strongest legal basis for this is Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union, which clearly states that if a member state is the victim of armed aggression, the other member states are obligated to provide all available aid and assistance,

he told us.

Lomnici noted that while the provision acknowledges each member state’s unique defense policy, the essence remains clear: an attack on one activates the security obligations of all, triggering collective legal responses.

When we apply this rule to Ukraine’s situation, the implications become starkly clear. Ukraine is currently engaged in an armed conflict; parts of its territory are outside its effective control, and hostilities are not isolated incidents but an ongoing reality of war. If Ukraine were to join the European Union under such conditions, Article 42 would make the war not a neighboring country’s problem, but an internal EU matter,

he said.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!