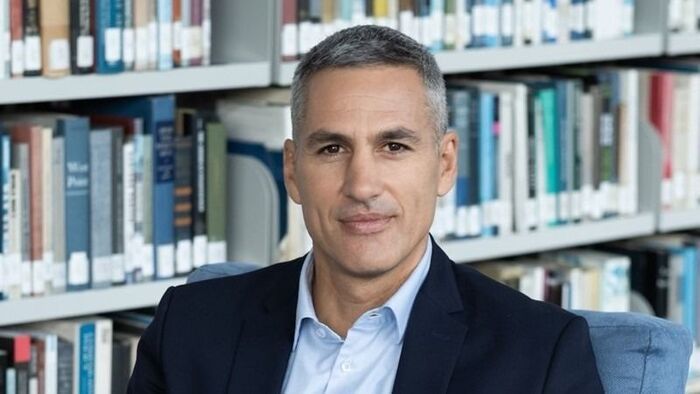

From the very beginning, the existence and functioning of the European project has been defined by fundamental EU principles and values. These are embodied and safeguarded "in one single institution": the member state veto right. The Treaty briefly defines this as "decisions of the European Council are taken by consensus unless the Treaties specify otherwise," explained Zoltan Lomnici Jr., commenting on the plan Ursula von der Leyen has recently floated.

The Treaty also stipulates that legislative acts cannot be adopted and, unless otherwise provided in the Treaties, the Council and the European Council shall act unanimously,

pointed out the expert.

Qualified majority, that is, bypassing consensus, is possible only in limited, explicitly listed exceptions. Even then, the 'emergency brake' applies: if a member state objects for vital national reasons, there is no vote, and the matter must be brought before the European Council,

he explained.

Broadening exceptions cannot be done through a simple political declaration either. Even the so-called passerelle clause under Article 31(3) requires unanimity in the European Council, and in military or defense matters it is excluded.

Shifting foreign policy decisions to qualified majority, effectively hollowing out the veto right, would require treaty amendment – which can only be achieved through the Article 48 TEU procedure.

As long as these provisions remain in force, Ursula von der Leyen's idea has no solid legal basis, and it would involve significant restrictions on member state sovereignty,

the expert emphasized.

The Union shall respect the equality of Member States before the Treaties as well as their national identities, inherent in their fundamental structures, political and constitutional,

Zoltan Lomnici Jr. cited the Treaty.

He pointed out that: "This provision excludes even the possibility in principle of changing the current decision-making mechanism to the detriment of any member state – especially without amending primary law."

Von der Leyen’s plan has no independent legal basis for altering the decision-making mechanism of the common foreign and security policy. Article 30(1) TEU explicitly sets out who may initiate in this field: any member state or the Union’s High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. The Commission may appear only in a supportive role,

the scientific director highlighted.

Therefore, he argued, the Commission President’s statements cannot be considered a legally grounded initiative but merely a political stance that disregards both the procedural framework enshrined in EU treaties and the constitutional protection of member state sovereignty.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!