On November 13, the European Parliament approved the climate regulation targeting a 90 percent emissions reduction by 2040. One of its key instruments would be a new emissions trading system, starting in 2028, applied to residential heating and cooling, transportation, and agricultural activity. In essence, this amounts to a carbon tax designed and imposed by Brussels to artificially raise fuel prices and increase the energy costs of households and farmers in order to reduce consumption.

The measure is difficult to justify with rational arguments. The EU is responsible for only 6 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, yet its citizens already pay significantly more for utilities and fuel than people living in other major regions of the world, Szazadveg writes.

Last year, household electricity tariffs in the EU were 60 percent higher and gas tariffs 125 percent higher than in the United States. Similar differences appear in fuel prices: in January this year, the price of one liter of fuel in the EU was twice that in the United States and 65 percent higher than in China.

As a result, Europe is one of the most expensive regions in the world, with high transportation costs feeding into the price of nearly every product.

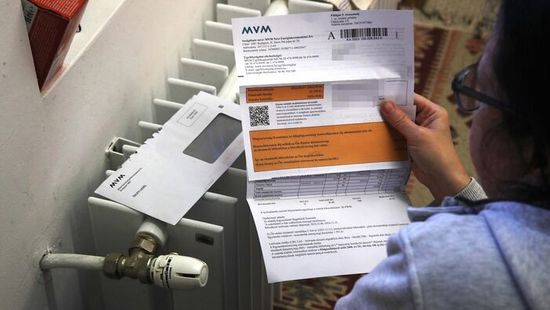

High energy prices also trigger severe social problems: in 2024, 22 percent of EU citizens reported difficulties heating their homes, and 26 percent struggled to pay their utility bills. Differences between countries can largely be explained by variations in tariff regulation. Hungary, for example, has been able to keep the share of affected households the lowest in the European Union because its utility price reduction scheme applies the strictest tariff regulation in the EU.

A technical prerequisite for introducing the emissions trading system is the elimination of regulated prices, which would immediately expose Hungarian households to full market rates. And to achieve the EU’s expected reductions in carbon emissions, further significant price increases would be required across the European Union, which would inevitably spill over into household tariffs. The harsher the state protection a country currently provides its citizens, the more drastic the impact would be: thus the most radical changes would hit Hungarian tariffs.

According to Szazadveg’s estimates, eliminating the utility price reduction program and introducing the carbon tax would push Hungarians’ electricity and gas tariffs to 3.9 times their current level, generating an annual extra cost of 575,000 forints for an average household. To meet Brussels’ radical climate targets, fuel prices would need to rise by nearly 50 percent in the first year alone. In Hungary this would set the new equilibrium gasoline price at 872 forints per liter, and diesel at 886 forints.

Alongside the dramatic rise in transportation expenses for households and shipping costs for companies, the carbon tax would also increase the cost of agricultural operations, combined with new carbon-related charges affecting other farming activities.

These new burdens would weaken the competitiveness of local agricultural businesses and push food prices higher—together with fuel market pressures—generating even greater inflation. Moreover, emissions reduction requirements will become continuously stricter, meaning the carbon tax, and therefore energy and fuel prices, would rise further year after year.

Szóljon hozzá!

Jelenleg csak a hozzászólások egy kis részét látja. Hozzászóláshoz és a további kommentek megtekintéséhez lépjen be, vagy regisztráljon!